05 Feb USPTO Grants Trademark for PSILOCYBIN, But Don’t Get Too Worked Up Yet

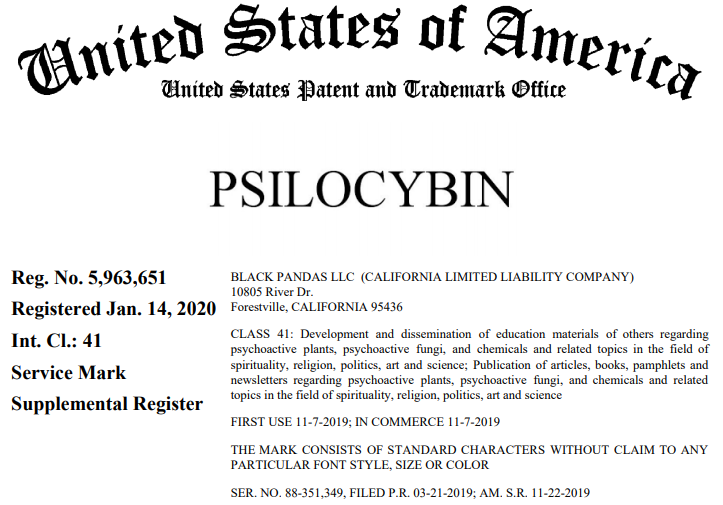

A few weeks back, Twitter was abuzz about the fact that the United State Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) granted a federal trademark registration for the word PSILOCYBIN. The mark was registered by the company Black Pandas LLC and applies to the following services in Class 041:

“Development and dissemination of education materials of others regarding psychoactive plants, psychoactive fungi, and chemicals and related topics in the field of spirituality, religion, politics, art and science; Publication of articles, books, pamphlets and newsletters regarding psychoactive plants, psychoactive fungi, and chemicals and related topics in the field of spirituality, religion, politics, art and science.”

First, it is important to note that the registration does NOT provide the registrant with exclusive rights to use the word “psilocybin” on all goods and services, and particularly not on goods that could be described as “psilocybin.” One of the requirements for federal trademark protection in the U.S. is that a mark is “distinctive.” Simply put, this means that a mark cannot be “merely descriptive” of the goods or services on which it is applied. So, for example, no one would be eligible to protect the word “psilocybin” for use on mushrooms, because this would be merely descriptive. It would be against public policy to limit the ability of other businesses and individuals to describe the goods they are selling (note that I’m setting aside the legality issues that come into play here, which are nearly identical to those faced by cannabis businesses attempting to procure federal trademark protection).

So, what happened here with the PSILOCYBIN registration? Initially, the examining attorney assigned to the file rejected the application under Section 2(e)(1) of the Trademark Act, meaning that she deemed the mark merely descriptive of the applicant’s services stating:

“Here, the term PSILOCYBIN is a naturally occurring psychedelic compound produced by various mushrooms. Applicant’s services feature materials regarding “psychoactive plants” and related topics; thus, the term PSILOCYBIN is descriptive of the subject matter of applicant’s services. Consumers encountering this mark – in the context of those services – will immediately understand the descriptive significance of the mark.”

However, in this case, the mark was only refused registration on the Principal Register. The examining attorney gave the applicant the opportunity to amend their application to seek registration on the Supplemental Register, so long as they could amend their application to show use in commerce.

Many trademark applicants are unaware of the existence of the Supplemental Register, let alone what it is. The Supplemental Register is “a second trademark register where trademarks can be registered that are not yet eligible for registration on the Principal Register, but may, over time, become an indicator of source. Marks registered on the Supplemental Register, like those registered on the Principal Register, are protected against conflicting marks in later-filed USPTO applications. However, Supplemental Register registrations do not receive the same legal advantages and presumptions of Principal Register registrations.”

What this means is that in a trademark dispute, the owner of a mark on the Supplemental Register does not enjoy a presumption of federal ownership. It’s much harder to win an infringement lawsuit with a Supplemental Register registration.

After five years of continuous use, an applicant for a mark that would otherwise be rejected for being merely descriptive can apply to register its mark on the Principal Register if it has additional proof of “acquired distinctiveness,” which can include evidence of notoriety, extensive advertisement of the mark, and declarations from third parties. A good example of a mark that made it onto the Principal Register through this process is SKATEBOARDER, which is a skateboard magazine. The mark would have been deemed merely descriptive and rejected, but the applicant was able to show sufficient notoriety over time to prove acquired distinctiveness.

It remains to be seen whether or not the PSILOCYBIN trademark will ever make it to the Principal Register. The more companies that begin to use the word “psilocybin” in conjunction with their online publications and services, the less likely it will be that the owner of this mark will be able to prove acquired distinctiveness five years from now.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.