01 Mar Channeling Anslinger: Cracks in a Crackpot Book About Pot

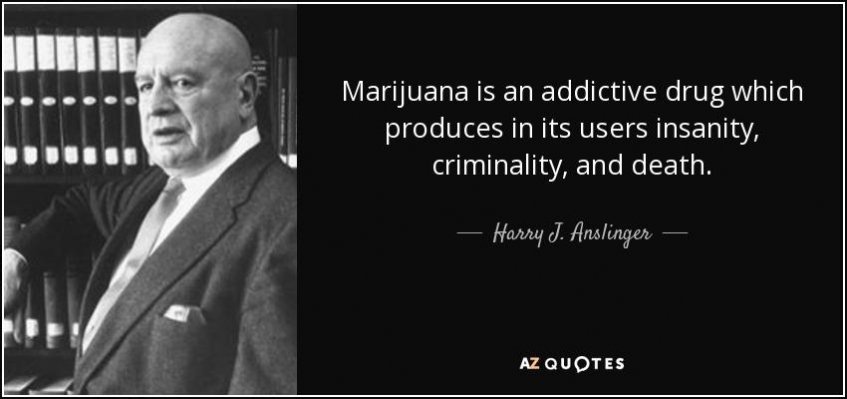

Alex Berenson, a science fiction author and former New York Times reporter, has written a book that would make Harry Anslinger blush. Anslinger, of course, was the longtime Federal Bureau of Narcotics director who waged a salacious, racially-charged sleaze campaign against marijuana, “the devil’s weed” that turned people into psychotic killers.

Entitled Tell Your Children: The Truth About Marijuana, Mental Illness and Violence (Free Press, 2019), Berenson’s screed resurrects many of the fact-free memes relentless promoted by Anslinger. It’s telling, if you’ll pardon the pun, that Tell Your Children was the original title of the notorious anti-marijuana propaganda film, Reefer Madness, released in 1936, which has since become a cult humor classic among cannabis consumers.

Apparently, Berenson didn’t get the joke. Nor did pop sociologist Malcolm Gladwell, who wrote a laudatory synopsis of Berenson’s book in The New Yorker.

Berenson and Gladwell question the scientific consensus that cannabis is one of the safest drugs available over or under the counter. As with any substance that may affect our health, cannabis can have both positive and negative effects, which should be thoroughly researched and monitored. But Berenson and Gladwell, who are not scientists and who display a glaring lack scientific and statistical literacy, are not interested in weighing the pros and cons of cannabis and assessing the evidence.

Instead, Berenson cherry-picks a worst-case, nightmare scenario, a theorized confabulation of inappropriately extrapolated science, where cannabis and its components cause mental illness and violence. The result is a crackpot argument that no scientist accepts, at least no scientists who were involved with the actual research being thrown about.

If you suspend disbelief and ignore all the positive evidence about cannabis, particularly its manifest health benefits, you end up with a sinister caricature. Berenson’s book is filled with misrepresentations and poor interpretations of research. He and Gladwell assume the worst any time there’s conflicting scientific data or research regarding potential harm that can’t be replicated. But if it can’t be replicated it means it may not be harmful.

Let’s deconstruct thematically some of the major flaws in this latest rendition of reefer madness.

Theme 1: Cannabis and mental illness – conflating association and cause.

The central methodology of Berenson’s book and the New Yorker article by Gladwell is to highlight research that suggests any association or link to cannabis and assume the link is causative. With that crucial predetermination, the plant becomes the de facto cause in any instance of a mental health disorder where cannabis is present in any amount. The attempt to attribute disease or a violent event to a single factor reeks of hereditarian and eugenic ideology, which reduces someone’s worth or potential to a single unit or factor.

But if there’s an association or correlation between cannabis use and mental health problems, it doesn’t necessarily mean that cannabis causes mental illness. Nor does it mean that mental health will improve if cannabis use is prevented. It could mean just the opposite – that mental illness causes people to consume cannabis as a form of self-medication.

“Spurious Correlations” is the name of a website – with lots of data from the Center for Disease Control and other sources – that aptly illustrates the folly of conflating association and causality. Google this website and you’ll find many examples of highly correlated phenomena that obviously are not causally related.

Case in point: Are you aware that there’s a 95 percent correlation between cheese sales and the number of people who’ve strangled themselves by their own bed sheets in the past 10 or 20 years? There’s also the classic example that links ice cream sales and drowning (both increase on hot summer days). These examples may demonstrate an association or link but perhaps are better explained by secondary correlations.

Theme 2: The high from THC causes paranoia, delusions and psychotic episodes that lead to violence.

Violence and mental health disorders are multifactorial. Berenson degrades and obfuscates our understanding of mental health and violent crime by blaming the consumption of cannabis for these problems. He ignores the role that factors such as family history of illness and one’s social environment and economic circumstances play in affecting many outcomes in a person’s life.

Promoted by Berenson and Gladwell, the assumption that cannabis causes mental health and violent crime narrows our creativity and prevents us from seeing potential solutions that lie outside of the scope of marijuana’s presumed nefarious influence. This does a huge disservice to our society. It is especially cruel to stigmatize people with mental health disorders as violent criminals.

The assumption of a causal link between cannabis and psychotic violence, while threadbare, is also unfalsifiable in a sense because it’s un-debunkable by clinical experiment. If you’re claiming that cannabis use is going to cause schizophrenia, then you can’t ethically give a person cannabis to test whether it actually causes schizophrenia.

In fact, there’s lots of good (albeit nonclinical) data that shows cannabis doesn’t cause schizophrenia. For starters, according to demographic analyses, the huge increase in cannabis consumption in the United States since the 1960s has not resulted in a parallel rise in cases of schizophrenia.

One can say that coffee causes people to be jittery if they drink too much. But no one contends that drinking a cup of coffee will give you attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Similarly, too much THC, while not fatal, can trigger transitory anxiety or paranoia, but that doesn’t mean THC causes mental illness. If a drug immediately triggers an experience or has an effect that mimics the symptom of a disease, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the drug causes that disease.

Violence, Psychosis & the Weather

Significant links, associations, and correlations are not proof of causation. Here are a number of factors – more so than cannabis – that are strongly associated with increases in violent crime and the risk of developing mental illness:

- There is a positive correlation between income inequality and crime rates (the U.S. ranks 3rd among the most income-unequal nations).

- Lower household income is associated with increased risk for mental illness.

- Violent crime increases when there is warm weather (regardless of the season).

- High intelligence is associated with developing mental illness.

- Increases in violent crimes are associated with increased access to liquor.

- Head injuries are strongly associated with developing mental illness.

- Increases in violent crime are associated with high blood pressure.

- Getting A grades in school are associated with an increased risk of developing bipolar disorder.

- Smoke from wildfires is associated with increases in violent crime and asthma.

- Consuming fast food, sugar and soft drinks is associated with a higher prevalence of ADHD.

- Lead exposure is associated with an increase in crime.

- Higher frequencies of common mental disorders (depression and anxiety) are associated with low educational attainment, material disadvantage and unemployment, and for older people, social isolation.

- Increases in violent crimes are associated with gentrification.

Theme 3: Cannabis is a gateway drug and it increases opioid use.

Even the Drug Enforcement Agency has changed its website information and now concedes there is not enough evidence to support the gateway theory. This is the theory that cannabis consumption inexorably leads to the use of other dangerous drugs.

Undaunted, Berenson and Gladwell (like the Japanese soldiers who emerged from the forest after 60 years of hiding and didn’t know the outcome of the war) have revived a quintessential drug war meme, the old gateway gag, the scientifically baseless contention that cannabis is a stepping stone to opiate addiction.

There is emerging evidence that cannabis use can be associated with a dramatic decrease in the use of prescription drugs like opiates and benzodiazepines. Scientific research supports the idea that cannabis may actually help people get off of opiates, alcohol and other drugs. Scientific data does not only undermines the gateway theory, it supports the opposite of Berenson’s worse-case scenario for cannabis.

It is true that some people who use cannabis will use other drugs later in life, maybe even develop substance use disorders. However, most clinicians and drug abuse researchers agree that smoking weed doesn’t drive one to use hard drugs. What drives people to use dangerous drugs has a lot more to do with stress, maladaptive coping mechanisms, and exposure to pharmaceutical drugs such as opioids and benzodiazepines rather than with a few puffs of the Funny Stuff.

Theme 4: We don’t know enough about the dangers of THC – and there’s a paucity of research supporting the FDA-approved therapeutic uses of THC and CBD.

Berenson and Gladwell dredge up the usual mishmash of unsupported claims: THC is inherently toxic, it damages the brain, and we don’t fully understand the negative impact of this malevolent molecule. They would have us believe that there have been no well-designed studies on cannabis products that show therapeutic benefits.

Again, the opposite is true. THC is one of the most widely studied drugs in history. Hundreds of peer-reviewed science articles have explored the neuroprotective effects of THC and CBD. There’s no evidence that THC and other cannabis compounds kill brain cells – but they can kill brain cancer cells. Preclinical research also shows that cannabinoids, including THC and CBD stimulate neurogenesis, the creation of new brain cells, in adult mammals.

THC has undergone rigorous testing and was approved in a purified form as “Marinol” by the FDA in the mid-1980’s. There are dosing guidelines for pharmaceutical THC and its abuse potential and risks are well established. Researchers had to do all that work, which Gladwell and Berenson denigrate, for THC to become an FDA-approved medicine.

Pharmaceutical THC is a Schedule III substance, a category reserved for medically useful drugs with minimal abuse potential. CBD is also an FDA approved medicine (Schedule V). And cannabis terpenes, the plant’s aromatic components, are generally regarded as safe (GRAS) by the FDA. If all the individual components of cannabis are legal in one form or another, then why is the plant still illegal? Don’t ask Berenson or Gladwell.

Diverting attention

For Berenson and Gladwell, it’s an article of faith that if you legalize cannabis, even just for medical patients, it will be easier for young people to access the evil weed and descend into the abyss. But the abuse potential of regulated, standardized cannabis products is minimal and pharmaceutical THC has virtually no value on the illicit market.

Ditto for Sativex, a sublingual tincture with a 1:1 THC:CBD ratio, which is legal in more than two dozen countries (but not yet in the United States). As with Marinol, there’s been little, if any, diversion of Sativex. The same cannot be said for a drug considered to be highly addictive such as Oxycontin, aka “hillbilly heroin,” which proliferates on the black market.

Gladwell and Berenson are unable or unwilling to distinguish differences in mental health outcomes when cannabis is used for medical and recreational purposes, or if cannabis products are acquired through a clinician’s supervision, a licensed dispensary or from the street. As far as they are concerned, therapeutic and recreational use are equally perilous.

In his article praising Berenson’s book, Gladwell compares always dangerous cannabis to “the once extraordinarily lethal innovation of the automobile [which] has been gradually tamed in the course of its history.” But no one has ever died from cannabis toxicity. And there’s obviously a big difference between using a nonlethal herb and zooming down the road in a metal box before pedestrians had any rights (the term J Walking was coined to defend the automobile industry). What makes Gladwell’s argument especially outrageous is that his analogy is more appropriate for describing opioids today when more Americans are likely to die from an opioid overdose than a car crash.

Uncontaminated cannabis

There are other ways to address public health concerns about cannabis rather than through prohibition and criminalization. Much of the danger attributed to cannabis and other illegal drugs comes from what they are contaminated with. Cannabis products would pose little threat to public health if sensible regulations and rigorous safety standards favored the creation of effective products free from contaminants.

Many hemp entrepreneurs and cannabis advocates want the industry to be well-regulated, taxed, and unionized. They want cannabis products to be clinically studied and to meet high standards in order to be covered by health insurance. For that to happen, cannabis would have to be rescheduled and decriminalized.

Instead of fixating on contrived nightmare scenarios, let’s flip the script and imagine what a best-case scenario might be. Rather than reflexively assuming that more cannabis research will expose as yet unverified harms, let’s assume the opposite. Let’s consider the possibility that if anachronistic research restrictions are removed, medical scientists will be able to validate promising anecdotal and preclinical reports by developing cannabis-based treatment options for many pathological conditions.

That would be something to tell your children.

Jahan Marcu, PhD, a Project CBD contributing writer, is the Director of Experimental Pharmacology and Behavioral Research at the International Research Center on Cannabis and Mental Health.

Further Reading: The Origins of Reefer Madness and The Return of Reefer Madness.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.