31 May Cannabis & the Bible

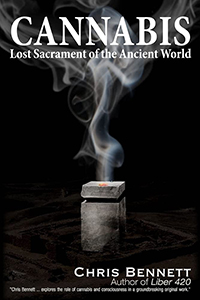

Biblical scholars have written about the role of cannabis as a sacrament in the ancient Near East and Middle East. Archeological evidence confirms the use of the plant in fumigation rituals in ancient Israel. Scriptural references indicate that cannabis was a key ingredient in the holy anointing oil employed in religious rites. But Yahweh, the Almighty Jealous God, frowned upon the idolatrous use of cannabis, the polytheistic drug of choice. The Old Testament chronicles the embrace of One God instead of many, a major shift that coincided with the displacement of cannabis as a ceremonial substance, as Chris Bennett reports in his latest book, Cannabis: Lost Sacrament of the Ancient World.

Humankind’s connection to cannabis reaches back tens of thousands of years. The role of cannabis in the ancient world was manifold: with its nutritious seeds, an important food; with its long, pliable strong stalks an important fiber; as well as an early medicine from its leaves and flowers; and then there are its psychoactive effects . . .

Due to its usefulness, cannabis has a very long history of human cultivation. How long, exactly, remains unknown. “No other plant has been with humans as long as hemp,” says ethnobotanist Christian Rätsch. “It is most certainly one of humanity’s oldest cultural objects. Wherever it was known, it was considered a functional, healing, inebriating, and aphrodisiac plant. Through the centuries, myths have arisen about this mysterious plant and its divine powers. Entire generations have revered it as sacred . . . . The power of hemp has been praised in hymns and prayers.”

The Great Leap Forward

There has been interesting scientific speculation that the psychoactive properties of cannabis played a role as a catalyst in the “Great Leap Forward,” a period of rapid advancement for prehistoric humanity, which started about 50,000 to 65,000 years ago. In their fascinating paper, “The Evolution of Cannabis and Coevolution with the Cannabinoid Receptor — A Hypothesis,” Dr. John M. McPartland and Geoffrey W. Guy explain how ingestion of this plant may have aided prehistoric humans. “In a hunter-gatherer society,” they write, “the ability of phytocannabinoids to improve smell, night vision, discern edge and enhance perception of color would improve evolutionary fitness of our species. Evolutionary fitness essentially mirrors reproductive success, and phytocannabinoids enhance the sensation of touch and the sense of rhythm, two sensual responses that may lead to increased replication rates.”

The authors postulate that plant compounds, which interact with the human body’s endocannabinoid system, “may exert sufficient selection pressure to maintain the gene for a receptor in an animal. If the plant ligand [plant-based cannabinoid] improves the fitness of the receptor by serving as a ‘proto-medicine’ or a performance-enhancing substance, the ligand-receptor association could be evolutionarily conserved.” In essence they are suggesting that there’s a coevolutionary relationship between “Man and Marijuana” — and that somehow as we have cultivated cannabis, it may have cultivated us, as well.

McPartland and Guy reference others who propose that cannabis was the catalyst that facilitated the emergence of syntactic language in Neolithic humans: “Language, in turn, probably caused what anthropologists call ‘the great leap forward’ in human behavior, when humans suddenly crafted better tools out of new materials (e.g. fishhooks from bone, spear handles from wood, rope from hemp), developed art (e.g. painting, pottery, musical instruments), began using boats, and they evolved intricate social (and religious) organizations . . . . This recent burst of human evolution has been described as epigenetic (beyond our genes) — could it be due to the effect of plant ligands?”

In his study on the botanical history of cannabis and man’s relationship with the plant, Mark Merlin, Professor of Botany at University of Hawaii, referred to hemp as one of “the progenitors of civilization.” Merlin was not alone in suggesting that hemp “was one of the original cultivated plants.” In The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence, the late Carl Sagan conjectured that early man may have begun the agricultural age by first planting hemp. Sagan, who was known to have a fondness for cannabis himself, cited the pygmies from southwest Africa to demonstrate his hypothesis. The pygmies had been basically hunters and gatherers until they began planting hemp, which they used for religious purposes. The pygmies themselves profess that at the beginning of time the gods gave them cannabis so they would be both “healthy and happy.”

Gift of the Gods

Professor Richard E. Schultes, of Harvard University, considered the father of modern ethnobotany, believed it was likely in the search for food that humanity first discovered cannabis and its protein-rich seeds. Today, hempseed products are touted as a modern “super food” due to their richness in essential fatty acids.

“Early man experimented with all plant materials that he could chew and could not have avoided discovering the properties of cannabis (marijuana), for in his quest for seeds and oil, he certainly ate the sticky tops of the plant,” Schultes has written. “Upon eating hemp, the euphoric, ecstatic, and hallucinatory aspects may have introduced man to the other-worldly plane from which emerged religious beliefs, perhaps even the concept of deity. The plant became accepted as a special gift of the gods, a sacred medium for communion with the spiritual world and as such it has remained in some cultures to the present.”

Archaeological evidence attests to this ancient relationship as well. A hemp rope dating back to 26,900 BC was found in Czechoslovakia; it’s the oldest evidence of hemp fiber. Hemp fiber imprints over 10,000 years old in pottery shards in Taiwan, and remnants of hemp cloth from 8,000 B.C. have been found at the site of the ancient settlement Catal Hüyük in Anatolia (modern day Turkey). Much older tools for breaking hemp stalk into fibers indicate humanity has been using cannabis for cloth “since 25,000 B.C. at least,” according to prehistoric textiles expert Elizabeth Wayland-Barber.

Cannabis was also among our first medicines. A recent study by Washington State University scientist Ed Hagen suggests that our prehistoric ancestors may have ingested cannabis as a means of killing of parasites, noting a similar practice among the primitive Aka of modern-day central Africa. We do know that references to cannabis medicine appear in the world’s oldest pharmacopeias, such as China’s Shennong Ben Cao Jing, in ancient Ayurvedic texts, in the medical papyrus of Egypt, in cuneiform medical recipes from Assyria, first on a list of medicinal plants in the Zoroastrian Zend Avesta, and elsewhere.

Holy Smokes!

Evidence of cannabis being burnt ritually is believed to date as far back as 3,500 BCE based on archaeological finds in the Ukraine and Romania. In Incense and Poison Ordeals in the Ancient Orient, Alan Godbey attributes the genesis of the concept of “divine plants” to “when the primeval savage discovered that the smoke of his cavern fire sometimes produced queer physiological effects. First reverencing these moods of his fire, he was not long in discovering that they were manifested only when certain weeds or sticks were included in his stock of fuel. After finding out which ones were responsible, he took to praying to these kind gods for more beautiful visions of the unseen world, or for more fervid inspiration.”

Various Biblical scholars have written about the role of cannabis as a sacrament in the ancient Near East and Middle East. The ancient Hebrews came into contact with many cultures — the Scythians, Persians, Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians, and Greeks — that consumed cannabis. And these cultures influenced the Hebrew’s use of the plant in fumigation rituals and as a key ingredient in the holy anointing oil applied as a topical to heal the sick and reward the righteous.

Compelling evidence of the ritual use of cannabis in ancient Israel was reported in a 2020 archaeological study, “Cannabis and Frankincense at the Judahite Shrine of Arad,” by the Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. The authors noted that two altars with burnt plant residues had been found in a shrine at an ancient Hebrew outpost in tel Arad. One of the altars tested for frankincense, a well-known Biblical herb, and the other altar tested positive for cannabis resin.

The research, expectedly, caused a storm of controversy, with Biblical historians, religious authorities, and other parties weighing in. An article in Haaretz, headlined “Holy Smoke | Ancient Israelites Used Cannabis as Temple Offering, Study Finds,” raised a key question: “If the ancient Israelites were joining in on the party, why doesn’t the Bible mention the use of cannabis as a substance used in rituals, just as it does numerous times for frankincense?”

The Disappearance of “Kaneh Bosm”

Actually, several scholars have drawn attention to indications of cannabis use in the Bible. Polish anthropologist and etymologist Sula Benet contends that the Hebrew terms kaneh and kaneh bosm refer to cannabis. Benet identified five specific references in the “Hebrew Bible” (aka the Old Testament) — Exodus 30:23, Song of Songs 4:14, Isaiah 43:24, Jeremiah 6:20, and Ezekiel 27:19 — that mention kaneh and kaneh bosm. However, when one reads these passages individually and compares them, a stark contrast emerges.

In Exodus 30:23, the reference is to an ingredient in the Holy Oil, which was used in the Holy of Holies, the inner chamber of the Temple in Jerusalem, whereas in Jeremiah 6:20, this same previously sacred substance is wholly rejected as an item of foreign influence and disdain. It appears that Yahweh, the Jealous God, frowned upon the idolatrous use of cannabis, the polytheistic drug of choice.

The identity of kaneh and kaneh bosm has long been a topic of speculation. Benet’s view was that when the Hebrew texts were translated into Greek for the Septuagint, a mistranslation took place, deeming it as the common marsh root “calamus.” This mistranslation followed into the Latin, and then English translations of the Hebrew Bible. It should be noted that other botanical mistranslations from the Hebrew to Greek in the Hebrew Bible have been exposed.

This article is adapted from Cannabis: Lost Sacrament of the Ancient World by Chris Bennett (TrineDay, 2023). Bennett is the author of several books, including Liber 420 and Cannabis and the Soma Solution. © Copyright, Project CBD. May not be reprinted without permission.

Recommended Readings

Excerpted from “Cannabis and Spirituality: An Explorer’s Guide to an Ancient Plant Spirit Ally,” edited by Stephen Gray.

Cannabis, the Euphoriant

Excerpted from “The Lotus and the Bud: Cannabis, Consciousness, and Yoga Practice” by Christopher S. Kilham.

Satchmo Visits Africa

Excerpted from “Smoke Signals: A Social History of Marijuana – Medical, Recreational, and Scientific” by Martin A. Lee.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.